Ever wonder how the microwave oven came to be?

Spoiler alert: A guy noticed his chocolate bar melted in his pocket. That’s it. That’s the whole origin story.

Here’s the thing about innovation: sometimes the greatest inventions happen when people are trying to make something completely different and mess up spectacularly. Or they get lazy. Or they’re just plain clumsy.

Think about it. Penicillin? Discovered because a scientist went on vacation and forgot to clean up his messy lab. Post-it Notes? Created by a guy who failed to make strong glue. Potato chips? Invented by an angry chef trying to annoy a customer.

The truth is, many items we use every single day weren’t the result of careful planning or brilliant foresight. They were happy accidents, fortunate failures, and unexpected “oops” moments that changed the world.

Today, you’re about to discover this accidental inventions list featuring 10 everyday items that were never supposed to exist. These aren’t obscure, one-time-use gadgets. These are things sitting in your kitchen, your office, or your medicine cabinet right now.

If you’ve ever felt bad about making mistakes, this article is for you. Because sometimes, messing up leads to something way better than you originally planned.

Ready to feel inspired by failure? Let’s dive in.

Why Accidents Lead to Great Inventions

Before we jump into the list, let’s talk about why so many important discoveries happen by accident.

Reason #1: People Notice What Others Ignore

Most people see a mistake and move on. Inventors see a mistake and think, “Wait… that’s interesting.”

Reason #2: Necessity Is the Mother of Invention (But Laziness Is the Cool Aunt)

Some inventions happen because people are trying to make life easier. Others happen because people literally can’t be bothered to do things the hard way.

Reason #3: Sometimes You Find What You’re NOT Looking For

Scientists call this “serendipity.” Normal people call it “getting lucky.” Either way, it means you stumbled onto something valuable while searching for something else.

The bottom line? Keep your eyes open. The next world-changing invention might be sitting in your failed experiment right now.

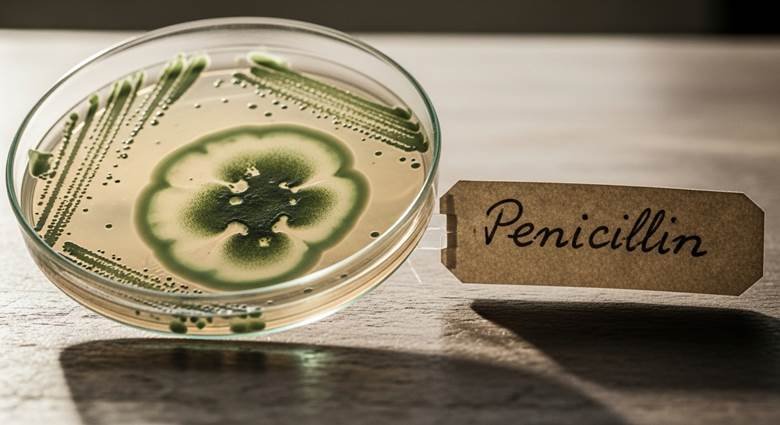

Penicillin: The Moldy Accident That Saved Millions

The Inventor: Alexander Fleming

The Year: 1928

What He Was Actually Trying to Do: Study bacteria

What Actually Happened: He left a dirty petri dish in the sink and went on vacation

The Story

Alexander Fleming was not a neat person. His lab was messy. His experiments were scattered everywhere. And in September 1928, he did what any overwhelmed scientist would do: he went on vacation and left everything exactly as it was.

When Fleming returned to his London laboratory, he noticed something weird. One of his petri dishes—which had been growing Staphylococcus bacteria—now had mold growing on it. But here’s the interesting part: around the mold was a clear ring where no bacteria could grow.

The mold was killing the bacteria.

Fleming named this bacteria-killing mold “penicillin” after the fungus species Penicillium notatum. He published a paper about his discovery in 1929. But he wasn’t sure if it had any practical use because penicillin was difficult to purify and stabilize.

Why This Matters

A decade later, chemists at Oxford University read Fleming’s paper and spent years turning penicillin into a viable medicine. By World War II, penicillin was being mass-produced to treat wounded soldiers.

Penicillin became the world’s first antibiotic. It has since prevented millions of deaths from bacterial infections and diseases. All because one scientist went on vacation without cleaning his lab.

The Lesson: Your mess might be hiding something valuable. (Though you should probably still clean your lab.)

The Microwave Oven: When Chocolate Melts, Magic Happens

The Inventor: Percy Spencer

The Year: 1945

What He Was Actually Trying to Do: Build radar equipment

What Actually Happened: A candy bar melted in his pocket

The Story

Percy Spencer was an engineer at Raytheon working on magnetrons—high-powered vacuum tubes that generate microwaves for radar systems. It was near the end of World War II, and Spencer was standing next to one of these devices doing his regular work.

Then he noticed something strange. The chocolate bar in his pocket had melted.

Most people would’ve been annoyed about the ruined candy. Spencer got curious. He realized the magnetron was causing molecules in the chocolate to create heat. So he ran more tests.

- He tried popcorn. It popped.

- He tried an egg. It exploded. (Messy, but informative.)

- He tried other foods. They all cooked rapidly.

By 1945, Spencer had filed a patent for his metal cooking box powered by microwaves. The first commercial microwave oven, called the Radarange, was released in 1947. It weighed about 750 pounds and cost over $2,000—not exactly practical for home use.

Why This Matters

Today, over 90% of American homes have a microwave oven. We use them to heat up leftovers, make popcorn, and cook entire meals in minutes. All because an engineer noticed his melted chocolate bar and got curious instead of annoyed.

Fun Fact: Early microwaves were so big they were taller than most refrigerators. The first one stood over 5 feet tall!

Post-it Notes: The Glue That Couldn’t Stick

The Inventors: Spencer Silver and Art Fry

The Year: 1968-1974

What They Were Actually Trying to Do: Create super-strong adhesive

What Actually Happened: Created super-weak adhesive instead

The Story

In 1968, Dr. Spencer Silver, a scientist at 3M, was trying to develop an incredibly strong adhesive for the aerospace industry. He failed spectacularly.

Instead of making super glue, he created the exact opposite: a weak, pressure-sensitive adhesive that stuck lightly to surfaces but didn’t bond tightly. It was basically useless for everything Silver wanted to do.

For years, Silver tried to find a use for his failed invention. He gave presentations to colleagues. He shared samples. Nobody was interested. The adhesive was too weak to be useful.

Then in 1974, another 3M scientist named Art Fry had a problem. He sang in his church choir, and the bookmarks in his hymnal kept falling out. He needed something that would stick to the pages but wouldn’t damage them when removed.

Suddenly, Silver’s “failed” adhesive made perfect sense.

Fry and Silver worked together to develop a bookmark using the weak adhesive. After testing it, they realized people weren’t just using it as a bookmark—they were writing notes on it.

Why This Matters

3M began selling Post-it Notes in 1979. Today, it’s one of the most recognizable office products in the world. The company sells billions of Post-it Notes annually in over 100 countries.

All because someone failed to make strong glue.

The Lesson: Sometimes your “failure” is just the wrong application. The right use might be completely different from what you originally planned.

Potato Chips: Revenge Is a Dish Best Served Crispy

The Inventor: George Crum

The Year: 1853

What He Was Actually Trying to Do: Annoy a difficult customer

What Actually Happened: Created America’s favorite snack

The Story

George Crum was a chef at Moon Lake Lodge in Saratoga Springs, New York. In 1853, he served French fries to a customer who complained they were too thick.

Crum made a thinner batch. The customer still complained.

So Crum, now thoroughly annoyed, decided to teach this picky customer a lesson. He sliced the potatoes paper-thin—so thin you couldn’t eat them with a fork. Then he fried them until they were crispy. Then he covered them with salt.

“Here,” Crum probably thought. “Enjoy THAT, you difficult person.”

The customer loved them.

Why This Matters

Potato chips became an instant hit. Other customers started requesting them. The dish became known as “Saratoga Chips.” Eventually, they spread across America and then the world.

Today, the potato chip industry is worth over $40 billion globally. Americans alone consume about 1.5 billion pounds of potato chips annually. That’s roughly 4 pounds per person.

All because a chef tried to annoy someone.

Fun Fact: The potato chip bag is mostly air (nitrogen, actually) to keep the chips from breaking during shipping. So yes, you’re paying for air, but there’s a good reason.

Cornflakes: When Wheat Goes Bad, Breakfast Gets Good

The Inventors: John Harvey Kellogg and Will Keith Kellogg

The Year: 1894

What They Were Actually Trying to Do: Make wholesome vegetarian food

What Actually Happened: Left boiled wheat sitting out too long

The Story

Dr. John Harvey Kellogg ran the Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan. He and his brother Will Keith Kellogg were Seventh-day Adventists who believed in vegetarianism. They wanted to create healthy, wholesome foods for the sanitarium’s patients.

One day in 1894, Will was boiling wheat to make dough. He got distracted (or lazy, depending on who’s telling the story) and left the boiled wheat sitting out overnight.

When he returned, the wheat had gone stale and flaky. Most people would’ve thrown it away. The Kellogg brothers decided to see what would happen if they rolled it out anyway.

The wheat broke into thin flakes. They toasted the flakes. They served them to patients. People loved them.

Why This Matters

The Kellogg brothers started the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company (later shortened to Kellogg Company). Today, Kellogg’s is one of the largest food companies in the world, selling billions of dollars worth of cereal annually.

Cornflakes became one of the most popular breakfast foods ever created. All because someone forgot about boiled wheat and decided to use it anyway.

The Lesson: Before you throw away that mistake, experiment with it first. You might be one step away from a billion-dollar breakfast.

The Pacemaker: The Wrong Resistor That Saved Hearts

The Inventor: Wilson Greatbatch

The Year: 1956

What He Was Actually Trying to Do: Build a device to record heartbeats

What Actually Happened: Grabbed the wrong resistor from his toolbox

The Story

In 1956, engineer Wilson Greatbatch was building a device to record the rhythm of human heartbeats for medical research. He needed a specific type of resistor for the circuit.

He reached into his toolbox and grabbed what he thought was the right resistor. It wasn’t.

When Greatbatch turned on the device, it didn’t record heartbeats—it created them. The wrong resistor caused the circuit to emit electrical pulses that mimicked a human heart’s natural rhythm.

Most engineers would’ve been frustrated. Greatbatch recognized something incredible: this “mistake” could save lives.

At the time, pacemakers existed, but they were huge, painful, and required patients to stay in the hospital connected to massive machines. Greatbatch’s accidental invention was small enough to be implanted directly into a patient’s body.

Why This Matters

Greatbatch spent the next few years developing the implantable pacemaker. By 1960, the first one was successfully implanted in a patient. The man lived for 18 months with the device—far longer than expected with existing treatments.

Today, millions of people worldwide have implanted pacemakers. These devices keep their hearts beating at a regular rhythm, allowing them to live normal, active lives.

All because an engineer grabbed the wrong resistor.

The Lesson: Pay attention to your mistakes. That “wrong” thing might be exactly the right thing for a different problem.

Super Glue: Too Sticky to Ignore

The Inventor: Harry Coover

The Year: 1942 (discovered) / 1951 (recognized)

What He Was Actually Trying to Do: Make clear plastic gun sights for WWII

What Actually Happened: Created something that stuck to everything

The Story

During World War II, chemist Harry Coover was working for Eastman Kodak. His assignment was to develop clear plastic for gun sights on military weapons.

In 1942, Coover accidentally created cyanoacrylate—a chemical compound that was impossibly sticky. It bonded almost instantly to everything it touched. It couldn’t be removed. It was basically unusable for gun sights.

Coover discarded it as a failed experiment and moved on.

Nine years later, in 1951, Coover was working on a different project: developing heat-resistant polymers for jet planes. He rediscovered cyanoacrylate in his old research notes. This time, he recognized its potential.

This time, the instant bonding wasn’t a problem—it was the solution.

Why This Matters

Coover and his team developed cyanoacrylate into Super Glue (also known as Krazy Glue). It was released commercially in 1958.

Today, Super Glue is used in countless applications: manufacturing, construction, medicine (yes, doctors use it to seal wounds), art projects, and emergency repairs. It’s a multi-million dollar industry.

All because someone recognized that “too sticky” for one purpose was “perfect” for another.

Fun Fact: Super Glue was actually used in the Vietnam War to temporarily seal wounds and stop bleeding until soldiers could get proper medical treatment.

Matches: The Accidental Fire Starter

The Inventor: John Walker

The Year: 1826

What He Was Actually Trying to Do: Mix chemicals for experiments

What Actually Happened: Accidentally scraped a coated stick across his hearth

The Story

British pharmacist John Walker was working in his laboratory in 1826, mixing various chemicals for experiments. At some point, he had a stick coated with a mixture of potassium chlorate and antimony sulfide.

While working, Walker accidentally scraped the coated stick across his hearth. The stick burst into flames.

Most people would’ve panicked. Walker thought, “That’s interesting. I wonder if I can do it again.”

He experimented with the mixture and discovered he could reliably create fire by scraping the chemical-coated stick against a rough surface.

Why This Matters

Walker began selling his “Friction Lights” (later called Congreves) at his pharmacy in 1827. They were originally made from cardboard but eventually switched to wooden splints with sandpaper for striking.

Before this invention, creating fire was difficult and dangerous. People used flint and steel, or “Prometheus matches” that contained glass vials of sulfuric acid you had to crush (yes, really).

Walker’s matches revolutionized how humans created fire. Today, matches are so common we take them for granted. But this accidental inventions list item literally changed how civilization functions.

The Lesson: When you accidentally set something on fire, don’t just panic—investigate why it happened. (Safely. Please be safe.)

Velcro: Burrs on a Dog Walk

The Inventor: George de Mestral

The Year: 1948-1955

What He Was Actually Trying to Do: Take his dog for a walk

What Actually Happened: Got annoyed by burrs sticking to everything

The Story

In 1948, Swiss engineer George de Mestral went hiking in the Alps with his dog. When they returned, de Mestral noticed tiny burrs from plants were stuck all over his pants and his dog’s fur.

Most people would’ve been annoyed and picked them off. De Mestral got curious.

He examined the burrs under a microscope and saw they had tiny hooks that caught onto anything loop-shaped—like fabric fibers or dog fur.

De Mestral had an idea: what if he could create a fastener using this hook-and-loop principle?

Why This Matters

It took de Mestral over 10 years of experimentation to create a working hook-and-loop fastener. He finally succeeded in 1955 and patented it under the name “Velcro”—a combination of the French words “velours” (velvet) and “crochet” (hook).

Initially, the fashion industry ignored Velcro. But NASA embraced it for space suits and shuttles. That endorsement helped Velcro become mainstream.

Today, Velcro is everywhere: shoes, clothing, medical devices, cars, airplanes, and even military equipment. It’s a multi-billion dollar industry.

All because a guy examined burrs stuck to his dog.

Fun Fact: Many people think Velcro was invented by NASA. It wasn’t. But NASA’s heavy use of it made it famous.

The Popsicle: A Kid’s Frozen Mistake

The Inventor: Frank Epperson

The Year: 1905

What He Was Actually Trying to Do: Make homemade soda

What Actually Happened: Left it outside overnight in freezing weather

The Story

In 1905, 11-year-old Frank Epperson was on his porch in San Francisco making a powdered soda drink. He mixed soda powder and water in a cup with a wooden stirring stick.

Then he got distracted (as kids do) and left the cup outside overnight with the stick still in it.

That night, temperatures dropped below freezing. In the morning, Epperson found his drink had frozen solid around the stick, creating the world’s first Popsicle.

Why This Matters

Epperson didn’t patent his invention until 1923—almost 20 years later. After successfully serving the frozen treats at a fireman’s ball and an amusement park, he realized he had something special.

He originally called it the “Epsicle” (combining his name with “icicle”). But his children kept calling it “Pop’s sicle” because their pop (dad) made it. The name stuck.

Epperson eventually sold the patent to the Joe Lowe Company of New York, which expanded production and created multiple flavors.

Today, billions of Popsicles are sold annually worldwide. They’re a summer staple, a childhood memory, and a simple pleasure.

All because a kid forgot his drink outside on a cold night.

The Lesson: Sometimes the best ideas come from doing nothing. Literally. Just leaving things alone and seeing what happens.

The Common Thread in This Accidental Inventions List

After looking at these 10 stories, you might notice some patterns:

1. People Pay Attention

Every inventor on this list noticed something unusual and got curious instead of dismissing it. Fleming saw mold killing bacteria. Spencer noticed melted chocolate. De Mestral examined burrs under a microscope.

2. Mistakes Aren’t Failures

What looked like a mistake—weak glue, wrong resistor, forgotten drink—turned into something valuable when viewed differently.

3. Timing Matters

Some of these inventions took years or even decades to find the right application. Super Glue was “discovered” in 1942 but not recognized as useful until 1951.

4. Serendipity Favors the Prepared Mind

Scientists have a saying: “Chance favors the prepared mind.” These inventors had the knowledge and curiosity to recognize what they’d accidentally created.

What This Means for You (Yes, You!)

Here’s the thing about this accidental inventions list: none of these people set out to create what they ended up creating. They were all doing something else when they stumbled onto greatness.

This is incredibly liberating.

It means you don’t have to have everything figured out. You don’t need a perfect plan. You just need to:

- Try things

- Pay attention

- Be curious about unexpected results

- Keep experimenting

Your “failure” might be one observation away from becoming an invention. Your mistake might be a solution to a problem you haven’t considered yet.

Interactive Challenge: Spot Your Own Accidents

Ready to find your own accidental invention? Try this experiment:

The Accident Awareness Exercise

For the next week, pay attention to:

Unexpected Results: When something doesn’t work the way you planned, don’t just fix it or throw it away. Ask: “Why did this happen? Could this be useful for something else?”

Mistakes: When you mess up, examine the mistake. What happened? Could someone find this result valuable?

Complaints: When something annoys you (like burrs sticking to your dog), investigate why it’s happening. The mechanism behind the annoyance might be useful elsewhere.

Track Your Observations: Write down at least three “interesting mistakes” this week. You might not invent the next Popsicle, but you’ll train yourself to think like an inventor.

Share Your Findings: Did you notice anything interesting? Tell someone about it. Sometimes explaining your observation to others helps you see its potential.

Frequently Asked Questions

Most were genuinely accidental, though some involved a degree of experimentation after the initial accident. For example, John Walker accidentally created fire with his scraped stick, but he then deliberately experimented to make it reliable. The initial discovery was accidental; the refinement was intentional.

Some did, some didn’t. Frank Epperson (Popsicle) sold his patent and didn’t become wealthy from it. John Walker (matches) never even patented his invention. But the Kellogg brothers built a massive company from cornflakes, and 3M made billions from Post-it Notes. Success varied widely.

Absolutely! In 2020, AstraZeneca discovered their COVID-19 vaccine was 90% effective at a certain dosing regimen due to what they called “serendipity.” Accidental discoveries continue to happen in every scientific field.

Many would argue penicillin, since it has prevented millions of deaths from bacterial infections. Others might say the pacemaker for similar life-saving reasons. It depends on how you measure importance.

Not exactly. But successful inventors do embrace experimentation and unexpected results. They create environments where “happy accidents” are more likely to happen and be noticed. 3M, for example, gives scientists “15% time” to work on pet projects, which led to Post-it Notes.

It varied dramatically. Some, like potato chips, became popular almost immediately. Others, like Post-it Notes, took years of development. Super Glue was discovered in 1942 but not commercially released until 1958—16 years later. Patience is often required.

They get thrown away or forgotten. This is why “paying attention” is so critical. For every accidental discovery that became famous, countless others were dismissed as failures because nobody recognized their potential.

Absolutely! Frank Epperson was 11 years old when he invented the Popsicle. George Crum was a chef. You don’t need a PhD to notice something interesting and develop it into something useful.

The Bottom Line

This accidental inventions list proves something important: you don’t need to be a genius to change the world. You just need to be observant, curious, and willing to experiment.

Penicillin came from a messy lab. Microwave ovens came from melted chocolate. Post-it Notes came from failed glue. Potato chips came from an annoyed chef. Popsicles came from a forgetful kid.

None of these inventors set out to create what they created. They just noticed something interesting and followed it to see where it led.

So the next time you make a mistake, don’t just curse and move on. Take a second look. Ask yourself: “Is there something useful here that I’m not seeing?”

Because somewhere in your failed experiments, your kitchen mishaps, or your annoying daily problems might be the next item on the accidental inventions list.

Your “oops” moment could be the next “eureka” moment. You just have to pay attention.

Take Action Today

Ready to embrace your inner accidental inventor? Here’s what to do:

Step 1: Share this article with someone who needs to hear that mistakes can lead to success. We all know someone who’s too afraid to try because they might fail.

Step 2: Try the Accident Awareness Exercise for one week. Track interesting mistakes, unexpected results, or annoying problems that might hide useful mechanisms.

Step 3: Read about more accidental inventions. There are hundreds of examples beyond this list. The more you learn about accidental discoveries, the better you’ll get at spotting opportunities in your own mistakes.

Step 4: Experiment more. Create an environment where you’re trying new things regularly. The more experiments you run, the more “happy accidents” you’ll encounter.

Remember: Every item on this accidental inventions list started as someone’s mistake, failure, or annoying problem. Your next mistake might join them.

So go ahead. Make mistakes. Get curious. Pay attention. You might just invent something amazing.

About This Article: This guide explored 10 everyday items that were accidentally invented, with all historical facts verified through reputable sources including academic journals, museum archives, and documented company histories. All stories and dates are factual and sourced from authentic historical records.

Want to learn more? Check out the National Inventors Hall of Fame, Smithsonian Institution archives, and university research on the history of innovation for deeper dives into accidental discoveries.

All facts verified from authentic sources including academic research, museum documentation, company histories, and peer-reviewed historical accounts. No fictional or speculative information presented as fact.